True Confessions

Some folks learn the hard way, and

yours truly is evidently a paid-up member of this unfortunate group.

Since this story is true, one might seriously consider including it in

selected culturally expansive works such as “The Evolution of the

English Language”. Then too, the content could well be used to

illustrate a point in a text pointing out the pitfalls awaiting radio operators

and/or traffic handlers who are endowed with a limited vocabulary.

It all

happened in 1942, shortly after the catastrophe at Pearl Harbor. As a fledgling member of a Signal

Aviation unit, I landed a job as a CW operator at what was then

Langleyfield, Virginia. Being relatively new at the radio operator’s

game, it was my very first experience in the lofty, highly sophisticated

atmosphere of a genuine fixed military radio station. I was more than

favorably impressed with the hardware, not to mention the mass of blinking

lights, which tended to give the entire scene a rather festive

atmosphere.

Imagine an operating position with not one, not two, but

four operational receivers! To top that, my fellow operators reminded

me that the transmitter was such a powerhouse that it was remoted at a

location several miles distant. By virtue of my exalted assignment, I

was to be master of a probably underpaid, but trustworthy transmitter

attendant who would readily jump at my beck and call to change frequency,

adjust input power, or change antennas. What a beautiful setup!

Not much money, but a whole lot of action and authority! I was

dutifully impressed.

It was no surprise

to old timers at the station when they discovered my code speed was not near

the existing norm. Could it be that other operators involved were

sending just a bit above my speed? Oh no! I reasoned that it

wasn't the speed, it was the fact that these undistinguished clods were

carelessly running their characters and words together, getting their dahs

and dits mixed up, and otherwise goofing off. In any event, I

initially got along OK by continually asking the distant operator to slow

down a little (or a lot).

As a major

point stressed in our training as traffic handlers, we were continually

reminded to place accuracy first and foremost. We were warned that

this was absolutely essential when handling traffic of great consequence-

such as matters of life or death. It was

about 9 PM on my second day on the job. I was alone in the station

copying a message from the net control in Baltimore. I didn't pay a

bit of attention to the actual content of messages; just did my best to get

the proper words on paper in a readable

format.

While copying one of the first

transmissions from Baltimore that evening, the word “dearth”

floated in over the air waves. If my recollection is precise, I

sputtered something like, “There is no such word!” “Did

I get it right?” “Wow,” I thought, “Maybe some

VIP kicked the bucket!” I desperately interrupted the

transmission of my distinguished associate in Baltimore asking that he

repeat the provocative word. He dutifully repeated what once again appeared

to be the word “dearth”. When I interrupted him still

another time, I swear he sent “dearth” again! As I demanded

still another repeat I began to wonder about the two beers I had consumed

earlier in the evening. Were those drinks really 3.2 alcohol, as

labeled? Anyway, I copied “dearth” again and let the

stream of code continue while I copied “dearth of

water”. Wondering if someone by

the name of Waters died, I sent “ditty dum dumditty” for the

umpteenth time. For some reason or other, the distant operator was now

becoming a bit temperamental. At this stage of the game, he proceeded to

send the word “lid” several times. Now I was really

confused! Of course I knew a lid was a cover for a bottle, can, box,

etc. However, I had no idea how “lid” tied in with the death

of Waters. By this time, my erstwhile friend in Baltimore was sending

all of five words per minute. I asked him to send “death”

again and again. I tried to enlighten him as to the correct spelling

of the word but he reacted as though he did not get the message. Then

too, he balked when I asked him how I might fit the word “lid” into

the message. Without any encouragement at all, he endlessly repeated

that strange and seemingly inappropriate three-letter word. He began

to sound as though he was about to go off the proverbial deep

end!

Well, to make a short story long,

it finally dawned on me that there just might be such a word as

“dearth” in the dictionary. I finally copied the entire

message (less the mysterious word “lid”) at about ten words

per. The distant operator, bless his soul, refused to send any

faster. To this day, I am not at all sure that this ten-word per guy

was the same operator I had been bugging earlier. Perhaps it was a

different fellow because I later heard a rumor that a certain Baltimore

brass pounder had been carried off to the funny farm while blabbering

incoherently about some “Lid at

Langley”.

After consulting a

dictionary, I finally deciphered the message. It had to do with the

dearth of water resulting from a recent drought. Since no dictionary

definition of the work “lid” seemed to fit the context of the

message, I forced myself to use elementary deduction to determine it’s

significance as it applied to yours truly. Another operator at Langley

joyfully and enthusiastically verified my suspicions. People have been

known to use four letter words with reference to your web page proprietor,

but this was the first time I had attained the lofty three-letter

plateau. I assure you that my new and unique moniker was not at all

complimentary!

Anyone for code

practice? If that doesn't suit your fancy, how about an in-depth

analysis of Websters New Collegiate Dictionary or, better yet, the unabridged

edition? Sounds like fun!

The Henry D. Thoreau

"It was

the Fall of 1943 and, as a fledgling 2nd Lieutenant, I was with my Army Signal Corps

unit, Company B of the 835th Signal Battalion, at Camp Shanks, N.Y. awaiting

shipment to the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations (CBI). While at

Shanks, I was surprised to receive orders to proceed to the port of Los Angeles at

Wilmington, California and accompany critical communications equipment to

the CBI. At the time, I wondered just what was expected of me during the

voyage? Was I to rescue the equipment in event we were

torpedoed? Guard against pilferage? Supervise handling to be

sure the critical items were not missent to the wrong address? I never

did get definitive guidance as to just what was expected of me; all I knew

was that the stuff had better show up overseas in an adequate condition!

Upon arriving

in Wilmington, I discovered that the equipment concerned was to be loaded

aboard the Liberty ship "Henry D Thoreau". The ship finally

sailed out of Los Angeles harbor on October 27th. Since, at that stage of the

war, the Japanese were in almost complete control of East Asia as far south

as the doorsteps to Australia, ships travelling unescorted from our West Coast to ports such as

Calcutta (our destination) were required to take an extreme southerly route

which took them very close to the South Pole.

It was almost

Thanksgiving as we approached our first port of call, Hobart,

Tasmania. Since it was my privilege to eat with the ship's officers, I

was privy to many conversations amongst them. I overheard the ship's

Chief Engineer tell the Captain that the main bearing in the ship's one and

only engine was badly worn and would not last the trip to Calcutta.

The Captain responded by reminding the Chief that his orders were to stop at

Hobart for fuel and water only. Now, like all the young and eager

fellows aboard, I was anxiously awaiting our call at Hobart with visions of

spending several days ashore eyeing the Australian beauties. Needless

to say, I was dejected beyond measure to hear of the Captain's position on

this matter.

As it turned out, we spent but one night in port.

Not nearly enough time for the crew and passengers to leave any kind of a social imprint Down Under! We

proceeded to sail south of Australia and then headed on a northwesterly course.

This track took us uncomfortably close to the Dutch East Indies, which at that

period in time were occupied by the enemy. As luck would have it, I

awoke one morning to a deathly silence aboard. It turned out that the

bearing had, in fact, collapsed leaving the ship without power in hostile

territory.

We bobbed about like a pitiful, defenseless cork for three

days while the ship's crew worked at installing a new main bearing. Luckily, they DID have one aboard! At least once each

day we could hear approaching aircraft. It was apparent that we were

not the only people aware of our plight! On each occasion, the

approaching craft were of the Royal Australian Air Force. If they had

been Japanese planes, this story would surely end differently!

After the three

hectic days, we were again underway with Colombo, Sri Lanka (known as Ceylon then) as our destination. It was at this port that we finally picked up a convoy and and a minimal escort for the remainder of the cruise to Calcutta via the Bay of Bengal.

A day or so out of Columbo, I was standing on deck overlooking the convoy in broad daylight when I saw the stern of a freighter rise up about 30 ft in the air with, of course, the screw showing as it twisted away... I did see the crew of the stricken ship scrambling to lower life boats but, since all ships in the convoy, other than the stricken craft, took off full steam ahead like a bunch of frightened hens, I didn't see much more. The wounded ship was sinking; that was obvious.

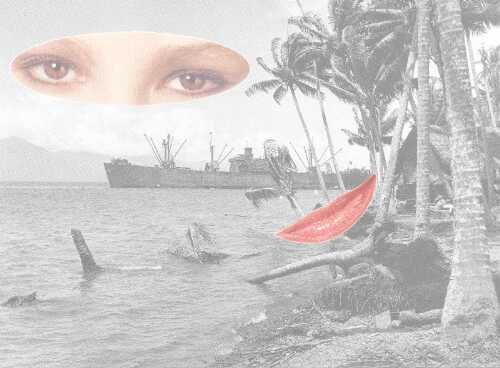

Take a gander at the picture below and get some idea as to my immediate reaction to this entirely unanticipated, intense, and otherwise shocking predicament!

No, I didn't jump overboard! We had what we called a British "Smokey Stover" as a Naval escort (It looked, to us, like a tug boat). Wouldn't you know that this protective element was no where to be seen before, during, or for about 2 hours after the incident? It is easy to imagine that the Japanese crew on the sub knew the escort was absent from the area accomplishing some other task. The Naval escort vessel was probably off to some Indian port for fuel or repairs. It was surprising to note that other ships in the convoy were hastily leaving the area. I had previously assumed that the ships would, under similar circumstances, stick together for mutual protection, but, come to think of it, remaining in a close-knit group like that would provide more juicy targets for submarines and/or enemy aircraft. The "Commodore" (convoy lead ship), being a fast passenger type, was out of sight over the horizon in no time... One can readily imagine where the Henry D. Thoreau was with it's 10 knot speed! Fortunately, the remainder of the trip to Calcutta was completed without incident.

The last I heard of the Henry D

was a news announcement on the radio in September, 1945. The news was

to the effect that the Henry D Thoreau was in distress in a Caribbean

storm. Highly explosive deck cargo had broken loose. Nothing

else was heard. I have often wondered just what had finally happened to this reliable, trusty old friend and her brave, devoted crew?

It is indeed sad and ironic if, after serving so gallantly during the war, the ship and its crew were victims of an unfortunate and deadly peace-time accident.

|